EPA studies vapor in Vernay site cleanup

- Published: September 7, 2017

Could vapors from an underground plume of toxic chemicals expose neighbors of a federal cleanup to dangerous levels of carcinogens, or are area residents safe from immediate and long-term harm?

That’s what the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency aims to find out in its latest request as part of a 15-year investigation into pollution at the Vernay Laboratories Inc. property on Dayton Street, the former site of its rubber products plant.

Two years ago, the EPA asked Vernay to start testing for vapors off-gassing from an underground plume of volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, in wells on its property. Later, tests were extended to wells on Dayton Street, Omar Circle, Wright Street, Suncrest Drive and Green Street and under some area residences.

Vernay has been under an order of consent with the EPA since 2002 to clean up the highly contaminated site, but the two parties have yet to agree on a final cleanup plan.

After its first round of underground vapor testing for soil gas in 2016, Vernay found “no evidence of vapor migration occurring at levels of concern for human health,” according to a recent progress report.

While three additional rounds of soil gas tests on- and off-property revealed three separate instances when a contaminant was measured above Ohio EPA response action levels, overall the tests are proving to the EPA that vapor intrusion is not an immediate danger to area residents.

“At the Vernay site, the sample data has not led EPA to conclude that vapor intrusion constitutes an immediate health threat,” the EPA wrote in an email this week.

The EPA revealed this week that Vernay also tested three private residences in April for vapor intrusion, measuring gas levels under slabs and crawl spaces. The EPA could not reveal the location of the residences, but only one had measurable contamination, and at a level that is “well below health protective EPA screening levels,” the EPA wrote this week.

“The sampling results at private residences support the conclusion that residents in the area are not being exposed to the chlorinated [chemicals of concern]” via vapor intrusion, the EPA wrote.

Oversight group raises alarm

The EPA’s conclusion is not shared by all parties connected with the cleanup, however. The fall 2016 readings from one soil gas test has a geologist involved in the oversight of the cleanup deeply concerned. It has led him to once again urge the EPA to order Vernay to promptly remove the contaminated soil from its property.

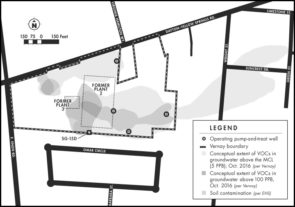

In a letter to the EPA in February, Michael Clinch of EHS Technology Group pointed to extremely high concentrations of contaminants in a soil gas well immediately north of residential property lines on Omar Circle (Click on map to enlarge). EHS is the firm hired to oversee the cleanup with funds from a lawsuit settlement between Vernay and a group of neighbors.

Groundwater contaminated with volatile organic compounds from operations at the former Vernay Laboratories production facilities on Dayton Street has spread eastward across Wright Street and Suncrest Drive. Soil contamination at the site is concentrated in an area near the two former plants, where chlorinated solvents used to degrease metal parts were disposed, and at the front of a property, where a common pesticide was used. SG-15D is the soil gas well whose fall 2016 high test results were alarming to the oversight firm EHS. (Map generated using data and maps from Vernay and EHS Technology Group)

Concentrations of tetrachloroethene (PCE), tricholoroethene (TCE) and vinyl chloride there far exceeded EPA Removal Management Levels for samples taken in both October and November 2016, and their impact should be considered cumulatively, Clinch wrote in the letter.

The results of the single well, “strongly show that a removal action is warranted,” Clinch wrote, later adding that “removing the soil that is the source of the contamination … is necessary to protect human health and the environment.”

Vernay was unable to test the SG-15D well in subsequent sampling rounds due to water in the well. The EPA has asked Vernay to try again this fall.

Vernay did not return multiple calls and emails seeking comment on its cleanup efforts.

TCE and PCE, two of the chemicals of concern, are chlorinated solvents that Vernay used for decades to degrease metal parts at the factory, according to EPA documents. The EPA considers TCE to be “carcinogenic to humans,” with links to cancers of the kidney, liver, cervix and lymphatic systems, while PCE is “likely carcinogenic” and impacts the nervous system and liver, according to the EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System. Vinyl chloride, a breakdown product of chlorinated solvents, is carcinogenic to the liver, according to the Center for Disease Control’s Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Other chemicals of concern in contaminated groundwater from the site are the VOCs cis-1,2 dichloroethene, which affects the cardiovascular and blood-forming systems and the liver, and 1,2-dichloropropane, which can damage blood-forming, neurological and respiratory systems along with the liver, according to the CDC’s ATSDR.

Vapor intrusion occurs when chemicals in soils and groundwater produce gases that percolate up and into the air, according to Ohio EPA spokesperson Dina Pierce. While the gases dissipate quickly outside, when they become trapped in buildings they can sicken occupants, she said.

“A lot of these VOCs are odorless and when they get into homes through cracks in basements or other pathways like pipes, there’s no way for them to escape,” Pierce added. Vapor intrusion can affect homes above or near a groundwater plume, according to EPA reports.

David Altman, the attorney representing the group of neighbors who settled with Vernay, said the fall 2016 soil gas readings are proof of vapor intrusion and should give the EPA cause to order a cleanup of contaminated soil at the property. Testing has gone on too long, Altman added this week.

“The boiling hot contaminated areas ought to be cleaned up,” Altman said. “Over the years we’ve been trying to get the U.S. EPA to order the cleanup. What they have been requiring Vernay to do is more testing, more testing, more testing.”

While the EPA is assuaged by the recent vapor intrusion test results, one neighbor involved in the lawsuit was concerned by what she sees as “very high risk levels” based upon the Fall 2016 test.

“I’m very concerned — vapor can go through sewers, pipes, crawl spaces and basements,” said Marcia Wallgren. “Vernay needs to do extensive testing. They need to clean up their mess.”

Other neighbors involved in the oversight didn’t return emails seeking comment or declined to go on the record with their concerns.

Vapor tests cause delay

The EPA’s growing understanding of the vapor intrusion threat over the last decade is one reason for the delay at the Vernay site, EPA Region 5 spokesperson Rafael Gonzalez said this week. A final cleanup plan for the Vernay site was originally expected in 2005, according to a 2003 EPA timeline.

“The work on a lot of these sites was put on hold because we knew a change was coming [in vapor intrusion standards],” Gonzalez said. “Now that we know we have a standard that will be around for a while we can move forward.”

After a final round of soil gas sampling takes place this fall, the agency and the company will resume discussions of the final cleanup plan, which Vernay first drafted in 2009, the EPA wrote this week. A final plan, known as a Corrective Measures Proposal, or CMP, may be ready for public comment by summer 2018, Gonzalez said. On that timeline, corrective measures could begin to be implemented in summer 2019.

Gonzalez denied that testing at the site has gone on too long.

“A lot of times it’s not easy to come up with the right answer and the right remediation process,” Gonzalez said. “They come up with their data and we come up with ours and there’s a lot of back and forth, a lot of negotiation.”

Beyond completing additional testing at EPA’s request, over the last 15 years Vernay has worked to monitor and contain contamination. This includes operating its four pump-and-treat wells on the property, two of which were added in 2011, sampling area groundwater and surface water outfall for contaminants twice each each year; and submitting quarterly progress reports to the EPA, which are available at the Yellow Springs Public Library.

To date, the pump-and-treat wells have carbon-filtered 147 million gallons of contaminated groundwater, according Vernay’s latest progress report. Vernay also annually surveys area residents with wells on their property and tests the wells. In 2016, four private water wells on Dayton Street were still in use, according to a 2016 progress report.

Vernay initially discovered contamination at its site in 1989 but waited nearly a decade to investigate the full extent and location of contamination, according to internal memos released by the Sierra Club in 2003. As part of the 2001 settlement agreement with neighbors, Vernay agreed to the U.S. EPA-supervised cleanup, signing an order of consent with the agency in 2002. Vernay also agreed to pay $850,000 in attorney fees for Altman, an undisclosed amount to plaintiffs, a $25,000 fine for violating the Clean Water Act and $455,000 to be used by plaintiffs for oversight of the cleanup.

Soil remediation, plume at issue

In recent years, the negotiation has brought to light disagreement among the three parties — EPA, Vernay and EHS — over whether any soil remediation should be part of a final cleanup plan and whether the plume is stable.

In its draft CMP, Vernay prefers a final plan in which it does not need to remediate the soil, but instead operates the pump-and-treat wells and waits for natural processes to break down the contaminants, which, according to EPA documents, could take more than 150 years.

Because of what the EPA considers an exceptionally long timeline, they have encouraged Vernay to not rule out soil remediation, according to EPA correspondence. However, this week the agency wrote that it “has not determined whether soil remediation at the Vernay facility is necessary to protect human health and the environment.”

Altman and Clinch of EHS meanwhile are pushing for soil remediation as the core of the cleanup. Altman sees the soil as “a red hot cauldron,” from which toxins are flushed into the groundwater by rain, a process he said was exacerbated by the 2009 razing of the site’s buildings.

The highest concentration of contaminants in soil at the site are found deeper than eight feet in the area between and under the two former plants, according to EHS maps. The location of the SG-15D well at the southern end of this highly contaminated area was not surprising, Altman said.

Another area of disagreement between the EPA and EHS is the status of the underground plume of contaminants in the shallow Cedarville aquifer, which starts 15 feet below the surface. In the most concentrated part of the underground plume, located near Vernay’s property and the former Rabbit Run Farm to its east, groundwater levels of VOCs exceed 100 ppb. The more diffuse section of the plume, where VOC levels exceed the EPA’s Maximum Contaminant Level of 5 ppb, extends across Wright Street and Suncrest Drive to Green Street. Contamination did not reach the deeper Brassfield aquifer, the source of Village municipal water two miles south, according to EPA documents.

According to Altman this week, Dr. Clinch does not believe the plume is stabilized and is still migrating eastward. The EPA however believes that concentrations of VOCs in the on-site and off-site bedrock groundwater plume have remained stable, and at some monitoring locations have declined over the last 10 years.

Next steps

The EPA wrote this week that Vernay and the agency have been working cooperatively to investigate pollution at the site and they expect cooperation to continue as they pivot toward a final cleanup plan. Ultimately, the EPA has the final say over what measures are included in the final cleanup plan under the 2002 order of consent, though Vernay could challenge the EPA’s decision in federal court, according to the EPA this week.

Altman said the group of neighbors could also seek a court action because of the long delay in cleaning up the property.

“It’s doing nothing that subverts the point of what these citizens went through,” Altman said of the lawsuit.

In the meantime, Pierce of the Ohio EPA said that area residents worried about the potential for vapor intrusion in their homes can contact the Dayton office of the Ohio EPA for a list of local environmental testing companies. To minimize the vapor intrusion risk, homeowners can also install venting systems similar to those used to mitigate radon.

Vernay is a 70-year-old local company that from 1951 to 2004 made rubber-molded parts for use in cars, appliances and medical equipment at its Dayton Street plants. Vernay now has plants in Georgia, Italy, the Netherlands, Japan, Singapore and China, and offices in France, Brazil and Korea, according to its website. While Vernay maintains a small R&D office on West South College Street in Yellow Springs at the site of its original facility, the global headquarters, formerly in Yellow Springs, is now in College Park, Ga.

[popup_trigger id=”71669″ tag=”span”]https://ysnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/083117_Vernay2col-1.jpg[/popup_trigger]

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.