Jim Agna: Showing up and taking a stand

- Published: February 16, 2017

ELDER STORIES

This series profiles Yellow Springs residents in their 80s and above. The News seeks to share older villagers’ stories and perspectives, honoring those who have lived long among us. If you have a story that fits our theme, contact us at ysnews@ysnews.com.

Articles in this series

- Elder Stories | Bruce Grimes’ 64 years of ‘Clayworks’

- Elder Stories | Sue Parker, always the good neighbor

- Elder Stories: Painter Jack Merrill

- Jane Baker: a life of books

- Always coming home to the village

- Fifty years in the same house

- Harold Wright— A bridger of words, and worlds

- Arnold Adoff: A shared life and love of literature

- Joan Horn: life as a doer, teacher and friend

- Jim Agna: Showing up and taking a stand

Jim Agna is a low-key and modest guy, so he probably won’t tell you that at many points in his career as a physcian, he’s been at the forefront of social change.

But his story indicates this is true. Agna’s presence on progressive front lines includes his work serving Antioch College students in the 1960s, when he was one of several doctors who provided the newly developed birth control pills to female students who requested them.

“Antioch College was one of the earliest colleges to offer reproductive health services,” he said in a recent interview.

The decision attracted national media attention, and Agna remembers fielding calls from the Wall Street Journal.

Those were also the years of growing drug use among young people, and again, the doctors serving Antioch College students were ahead of their time. Hallucinogenic drugs were popular on campus, especially after psychedelic gurus (and Harvard researchers) Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass) spoke on campus, according to Agna.

But Antioch students didn’t always have the ecstatic LSD experiences that Leary and Alpert described, so college physicians, including Agna, came up with a system to help those on a bad trip. The point wasn’t to punish the young people but rather to keep them safe, Agna said, so doctors at the Yellow Springs Clinic, where he worked, reserved a special room at the clinic for those having difficult psychedelic experiences, until the acid or mushrooms wore off.

It was important that the room was on the first floor, Agna said.

“We needed to have it on street level so no one jumped out the window,” he said.

Agna also became, in the early 1960s, the public face in southwestern Ohio for physicians who supported Medicare, which at the time was the newly proposed single-payer health program for elders. Medicare received little support from doctors, Agna said, comparing the Medicare controversy to the current controversy over Obamacare. Since Medicare seemed to benefit patients, Agna never could understand physicians’ opposition, and he found himself defending Medicare at a Cincinnati public debate with the head of the Medical Society.

“He said what I was saying reminded him of Krushchev,” Agna said, still shaking his head in wonderment 50 years later.

For Agna’s longtime friends David and Esther Battle, his stance on controversial issues provided a “moral compass” for those who knew him.

“His idealism is admirable and infectious,” the Battles wrote in an email. “He is informed, speaks out and takes action on national politics, civil rights, the need for a universal health system in the U.S., and other important issues … He expresses his opinions firmly but not aggressively. His presence in Yellow Springs is a significant reason that we feel proud to be members of this community.”

The 60s were just one component of the full and rich life that Agna has lived, much of it in Yellow Springs. When he first came to work at the Yellow Springs Clinic in 1959, Agna and his wife, Mary, who was also a physician, had five children. The family purchased the imposing red brick mansion on Xenia Avenue formerly owned by Senator Simeon Fess (and later by Vie Design Studio). But right before the Agnas moved to the village, the building had been used as a funeral home.

“Word got around that the new doctors bought the funeral home,” he said. “That made a big splash in town.”

Initially, Mary Agna stayed home raising the couple’s five children, but she soon began her own career in public health, serving as the Clark County Health Commissioner, and later Greene County Health Commissioner. A female physician was unusual for the time, and the Agna children remember a lively household with two engaged, intelligent parents who held similar values and concerns.

“My parents were very thoughtful and progressive, and it’s hard to think of stories that are just about my dad. They were inseparable, classic ‘finishers of each others’ sentences’ types,” their daughter, Gwen Agna, recently wrote via email. “They shared careers, politics, passions (single-payer health care and civil rights in particular). Growing up in the house on Xenia Avenue meant dinner together every night, by candlelight because there were no electric lights in the dining room, and serious conversations about the state of the nation and the world, with my mom at one end of the table and my dad at the other.”

In Yellow Springs, the Agnas lived their progressive values in a variety of ways. The couple opened their home to Sam Taylor, an African-American high school student from Farmville, Va., when that town closed its schools rather than integrate. Sam lived with the Agnas for two years, becoming a beloved member of the family, although his presence sometimes brought challenges from the extended family.

“Sam’s presence as a full member of the family was so important to our whole family,” Gwen Agna wrote. “So it was particularly confusing and hurtful when my grandmother (my dad’s mom) wouldn’t host Thanksgiving at their home as had been the tradition because she didn’t want the neighbors to see Sam walk into her house. I could see the sadness in my dad’s eyes in explaining this to us, but there was never a question that Sam would be with us for the holiday.”

Agna links his progressive values to having been a child in Troy, Ohio, during the Depression, witnessing his parents having to move in with his grandparents, a situation that made him keenly aware of income inequality. He also learned early about racial discrimination, as parts of Troy were segregated, and his good friend and high school tennis partner was an African American who educated Agna on “the subtleties of discrimination.”

After graduating from high school at age 16, Agna went to Purdue University, initially to study engineering. But World War II was still raging and the Navy, looking for doctors, offered to pay for medical school. So Agna decided to pursue pre-medicine instead, and he found his life’s calling.

And in medical school at the University of Cincinnati, he also found his life partner. Mary was one of about five female students out of a class of about 80, Agna said, and she worked her whole life to correct the gender imbalance in medical schools. She served on the admissions committee of Wright State until almost the end of her life, and was proud of having helped to achieve the goal of creating a medical school in which half of the students were female.

After graduating from medical school, Jim went to Rangoon, Burma (now Myanmar) to work with infectious diseases. Mary followed a year later after she graduated, working in an infant and maternal welfare clinic.

In a letter to a superior, Jim Agna described his first impressions of the country:

“Rangoon still has many scars of World War II. There are many bombed out buildings throughout the city. The population has swelled because of the influx of refugees from outlying areas. These refugees have sought security from insurgents who control a good portion of the country. The streets are crowded with vendors and beggars and many of the former fine residential areas are crowded with bamboo shacks of every description. The ample quantities of refuse about the streets together with a fair number of open sewers necessitates an olfactory adjustment for new arrivals …”

While the country was devastated in many ways, its Buddhist culture, with Buddhism’s “gentle, present-oriented” philosophy, made a lasting impact on Agna, he said in an earlier interview with the News.

After several years in Burma, the Agnas returned to Cincinnati to join the medical school faculty. And in the late 1950s, the family, now with several children, moved to Haiti, where Jim served for two years as medical director of the Hospital Albert Schweitzer.

The Agnas’ choices during this decade raised eyebrows among family members, Jim Agna said.

“We took on some challenges,” he said. “We did a lot of things that made our parents think we were out of our minds.”

Next came the move to Yellow Springs, and Jim’s work at the Yellow Springs Clinic. He and Mary were attracted by the clinic’s equitable philosophy in which all physicians, whether pediatricians, general practitioners or surgeons, were paid the same salary. It was a robust practice, and at the time Yellow Springs had about 12 doctors in all, including Harry Berley and Carl Hyde from Community Physicians. Patients came from all over Greene County and Springfield as well as Yellow Springs, Agna said.

But after a decade of Agna working in family practice, the University of Cincinnati came calling, offering both Agnas faculty positions at the medical school, so the family moved back to Cincinnati.

But after 10 years in Cincinnati the couple grew weary of suburban life, and when Wright State University opened its doors and they were offered jobs at the new medical school, they said yes. Especially appealing, according to Jim, was the opportunity to move back to Yellow Springs, which the couple had missed. They bought the house on Orton Road where they lived for the next several decades.

“It was the best of both worlds,” Agna said of living in the village and at the same time having jobs as medical school faculty.

At Wright State Jim was professor of medicine and later professor of postgraduate medicine and continuing education before he retired in 1988. But the leisurely life didn’t take, and when Hospice of Dayton vice-president Carol Dixon, who also lived in Yellow Springs, asked him to join the hospice staff, he agreed.

“She thought I was drinking too much coffee at the Emporium,” he said of Dixon.

As with other periods in his life, Agna found himself at the edge of social change, although this change was less dramatic than that of the 60s. But the hospice movement was new in this country, and many friends and relatives couldn’t understand why he’d choose to work in a place so “depressing.”

But Agna didn’t find it depressing. Rather, he found the atmosphere of patient-focused, palliative care to be life-affirming. And the hospice philosophy of helping people live fully to their last days helped Agna himself to find more joy and equanimity in his life, he said in the earlier News article.

Both Mary and Jim Agna retired in the mid-1990s. While Mary continued her public health work as a member of Governor Richard Celeste’s State Board of Health, Jim took life a bit easier. But he remained active in the community, reading to kids at Mills Lawn School and driving seniors to medical appointments, among many other activities.

But Agna is slowing down. Mary died almost exactly two years ago, and after 65 years of a close, happy marriage, it’s been a challenge.

“It’s a hard adjustment,” he said. “I take it one day at a time.”

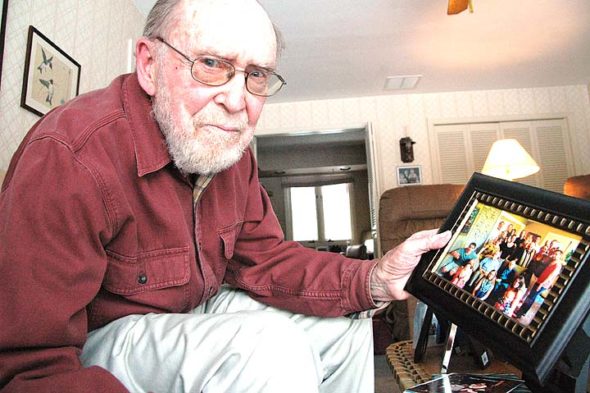

His Meadow Lane home — he and Mary sold the Orton Road home to their daughter, Molly, and her husband when they moved back to town — is filled with remembrances of his long, active life. There’s original artwork from Burma and Haiti, along with photos of the couple’s five children, nine grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Agna enjoys talking about his children and their varied and interesting lives: Gwen is a school principal in Northampton, Mass.; Tom a comedy writer who now lives in Thailand; Bridget a translator of Slavic languages in New York City; Molly an employee of Town Drug in Yellow Springs; and Jake, a tennis pro in Burlington, Vt. He remains an avid reader and thinker, daily reading the New York Times while keeping up regularly with the New Yorker and The Nation. His love of reading is also evident in the books piled on tables throughout the house.

As a kid, Agna felt special because his birthday, Feb. 12, was a national holiday and everyone got to stay home from school (it’s also Lincoln’s birthday). That birthday is coming up next week, when he’ll turn 91. On his birthday, as every other day, he’ll go downtown to pick up his Times from the Emporium, get some coffee, say hello to the people he sees and maybe do some shopping at Tom’s Market and Current Cuisine. Agna cites the Woody Allen quote that, “80 percent of success is just showing up.” He’s happy to say that he’s still showing up.

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

No comments yet for this article.