Xenia Avenue looking north in the early years of the automobile, with a streetcar line running down the middle of the road. At right is a building erected by the Independent Order of Odd Fellows in 1894 that has mostly housed the local pharmacy. (Photo courtesy of Yellow Springs Heritage)

A historical walking tour of downtown Yellow Springs

- Published: March 29, 2022

The following article appeared in the 2020–21 Guide to Yellow Springs: Downtown, Then and Now. Click here to read more articles from that year’s guide.

By Robin Heise

Editor’s Note: Greene County archivist Robin Heise has organized several historical walking tours through the village in recent years as part of one of her organizations, Yellow Springs Heritage. The following information was presented for a walking tour of downtown businesses a few years ago.

* * *

Before Yellow Springs was incorporated, it had several other names, including Ludlow and Forest Village. In 1853, William Mills marked off the initial 436 lots on 37 streets of Forest Village, which was incorporated into the Village of Yellow Springs in 1856. Mills had hoped that Yellow Springs would eventually become a bustling town of 10,000 people.

Also in 1853, Antioch College opened its doors to students, with Horace Mann serving as its first president. Mann was known as the “father of public education” and an abolitionist. In 1862, the Rev. Moncure Daniel Conway arrived in town with a group of Black citizens formerly enslaved in Virginia, who he believed could live a safe and prosperous life here in Yellow Springs.

Over the years, Yellow Springs has been a place for new beginnings and for rejuvenation. The healing waters of the Yellow Spring, source of the the village’s name, spurred the development of resorts and health spas in the 19th century. Today the village has about 3,700 residents.

Independent Order of Odd Fellows

The Independent Order of Odd Fellows (I.O.O.F.) is one of Yellow Springs’ oldest fraternal organizations. The Yellow Springs Lodge No. 279 was instituted on May 21, 1855. This building, however, was not built until 1894.

According to an 1894 newspaper article, the original IOOF building was in the planning stages. Early plans indicated that the building would be brick, two stories high, 20½ feet of frontage, 55 or 60 feet long, and fireproof. According to the article, the precautions taken during the construction would allow the lodge to save $150 a year in insurance. The first floor was planned to be rented to a local business, and the upstairs would be used for offices, and at the time of the 1894 newspaper article, the rooms had already been rented in advance. The downstairs has been a pharmacy for most of its history.

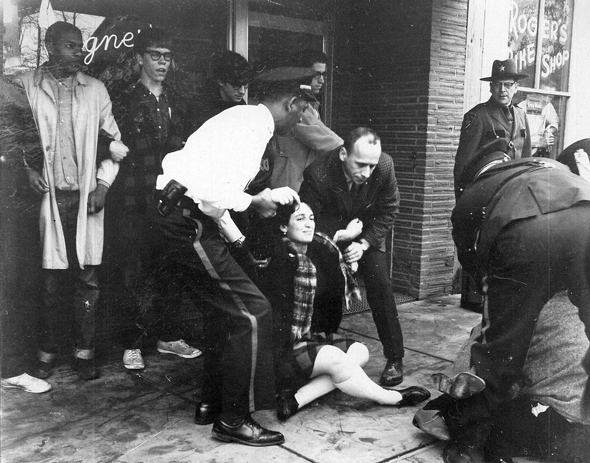

Police attempted to remove a protester in front of the Gegner Barbershop in 1964. Demonstrations against the local barber, who refused to cut the hair of Black people, escalated until a dramatic confrontation between 200 protesters and 150 area law enforcement on March 14, 1964. (Photo from the YS News archives)

Gegner’s barbershop

Now Yellow Springer Tees

Downtown Yellow Springs was the scene of a dramatic 1964 confrontation between police and protesters at the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Although Yellow Springs had the reputation as an open and welcoming community, it was really a microcosm of the segregated U.S. at the time. In the 1940s, the Little Theatre, now the Little Art Theatre, forced Black patrons to sit behind a rope in the back of the theater; the Glen Café and Ye Olde Trail Tavern refused to serve African Americans; and none of the village’s three barbershops would cut a Black person’s hair.

Over the next 20 years, a local citizens group successfully pressured most local businesses to accept Black patrons through boycotts, picketing, civil disobedience, court action and the passing of an anti-discrimination ordinance. By 1960, Lewis Gegner’s barbershop was the lone holdout.

In 1961, local resident Paul Graham, who is Black, entered the shop and asked for a haircut. Gegner refused, saying that he didn’t know how to cut his hair. Gegner was fined $1 for violating a Village anti-discrimination ordinance. But Graham then filed a complaint against Gegner’s discriminatory practices with the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, which issued a cease-and-desist order. Gegner appealed to the Greene County Court of Appeals and won, but Graham won at the district level, and the case was set to come before the Ohio Supreme Court in the first test of Ohio’s anti-discrimination ordinance since it was passed in 1878.

But community members and some Antioch students (specifically the Antioch Committee for Racial Equality), were growing increasingly frustrated. So in April 1963, they protested. It began simply, with two students picketing in front of the shop and handing out fliers. Meanwhile, African American students continued to enter the barbershop and ask for haircuts. Gegner refused them.

This continued into 1964. Gegner and the downtown merchants, claiming that the protests were hurting business, won an injunction at the Greene County Court that limited protestors to no more than three at a time. To continue picketing in large numbers, the activists would have to disobey the law. A large action was planned for Saturday, March 14, 1964. Two-hundred citizens marched into Xenia Avenue, locked arms and formed a barrier 10 people deep in front of Gegner’s shop.

Over 150 law enforcement officials from three counties used tear gas and fire hoses to disperse the demonstrators. By 4 p.m., Montgomery County police read the Ohio Riot Act and a line of officers, with their nightsticks, descended on the crowd. A local resident encouraged the group to disperse, but 108 people were arrested.

While the day was chaotic, it is an important part of our village’s history. Almost immediately after the protest, various groups began to sit down and have frank discussions of how to move forward.

After a solidarity march, Antioch and the Village held public discussions and the Human Relations Committee organized efforts to address the issues of equal rights, fair employment, integrated housing and other issues.

Three months after the demonstration, the 1964 Civil Rights Act became the first federal law requiring all businesses to serve the public regardless of race. Gegner’s shop never reopened. He sold his business in July 1964 and later moved away from the village.

Built around 1853, these are among the oldest buildings downtown. This photo was taken in 1975. (Photo courtesy of the Dayton Daily News)

First library

Now Yellow Springs Hardware

The DeNormandie Building, named after its owner Elizabeth DeNormandie, was built around 1853. In 1880, DeNormandie ran a 99-cent store in the building and lived in the brick home next door.

In 1899, the women of the Social Culture Club were trying to encourage the young people of Yellow Springs to read. The Social Culture Club decided that Yellow Springs needed a library, but there seemed to be no place to put one. The club rented a room in the corner of the first floor of this building. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union provided furniture in exchange for use of the room for its bimonthly meetings.

The Social Culture Club began filling the shelves of the reading room. They did this by going door-to-door throughout the village asking for magazines for their new reading room. When the room finally opened to the public, everyone who attended the opening was required to bring a book that would become a part of the permanent collection. By March 31, 1899, the library’s collection contained approximately 77 volumes, along with a few old magazines and newspapers. By 1906, the library had outgrown its one room and moved to the upper floors of the building.

As for the DeNormandie family home next door, that building later became a hotel, and is now a toy shop, Yellow Springs Toy Company. The hotel, the Comfort Inn (not to be confused with the chain of the same name), was owned by Zella Carper and operated from 1915 to 1950.

The building at 220 Xenia Ave. was the longtime home of the Antioch Bookplate Company, founded by Ernest Morgan, as well as the Yellow Springs News, which was published by Ernest and his wife Elizabeth during the 1940s. (Photo from the 1956 book, “Why They Came”)

Antioch Bookplate Co.

Now Jennifer’s Touch/Bonadies/Toxic Beauty

Antioch Bookplate Company was started as a co-op by two Antioch students and grew to an international company with hundreds of millions in annual sales.

One of the students, Ernest Morgan, was the son of Arthur Morgan, who became president of Antioch College, and a well-known engineer who had helped to construct the dam system in Dayton after the 1913 flood. While working in the Antioch print shop, Ernest found a creative use for the scraps of paper by refashioning them as decorative bookplates.

In 1926, Ernest, along with classmate Walter Kahoe, founded the Antioch Bookplate Company. Ernest initially sold the bookplates as a traveling salesman. The company continued to grow, moving into the building at 220 Xenia Ave. in 1931. By 1959, they were producing 90% of the world’s bookplates.

During the Depression, Ernest and his father, Arthur, founded the Midwest Exchange in the building. The Midwest Exchange was a community-based organization where goods and services were offered on barter. Unfortunately, the exchange only lasted about a year due to federal regulations that prevented such a program. For a time, the Yellow Springs News offices were also in the building. Between 1942 and 1949, Ernest was the editor and co-publisher of the News (along with his wife, Elizabeth), a co-founder of the Yellow Springs Community Credit Union and a founding member of the local committee for racial equality.

In 1974, Antioch Bookplate outgrew its facility and moved to 888 Dayton St.

Sales swelled to more than $340 million by 2003 with the success of a scrapbooking division. The company has since closed its Yellow Springs plant and gone out of business, while the scrapbooking division continues under new ownership.

Local photographer Axel Bahnsen took this photo of the Yellow Springs post office mid-century. (Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College)

Yellow Springs Post Office

This building has been used as a post office since it was built in 1940.

The post office contains a 1941 mural painted by New York artist Axel Horn, entitled “Yellow Springs: Preparation for Life Work.” This mural was part of a New Deal Treasury Department-funded program. Between 1933 and 1943, the government employed 10,000 artists.

It was determined that the post office was a common link between individuals, communities and the federal government. Some 1,100 murals which were selected through regional competitions went up in post offices across the country.

Each mural was to be a reflection of the local community. The Yellow Springs mural depicts a young man laboring at the edge of a field, having just cut down a large tree with the axe at his side. He is sitting on the tree reading a book, and wearing a hat and a sports coat. This mural was inspired by Antioch College, which had a well-known co-op program where students would take five years to graduate with a liberal arts education, but would alternate classroom study with work in an industry closely linked to their major.

A fire on May 5, 1895, devastated the Dayton Street and Corry Street business districts. Many businesses later rebuilt on Xenia Avenue. (Photo courtesy of Yellow Springs Historical Society)

Dayton Street/1895 fire

Dayton Street was the hub of the retail establishments in Yellow Springs until a fire in May 1895 destroyed much of the area.

According to the May 10, 1895, edition of the Yellow Springs Torch, “The greatest conflagration that ever visited Yellow Springs came in devastating fury … leaving in its track a depleted mass of ruins, blackened chimney stacks, dismal ghosts of trees stripped of fresh tender foliage of Spring, and yawning holes filled with twisted scarred iron roofage and heaps of smoldering ashes to mark the place where a whole block of buildings once stood; wiping out in a brief space of time, historic landmarks of the town, as well as some buildings which had stood as instruments of local enterprise and progress; changing in a twinkling and for all time, the whole appearance of the village as she used to be, but never will be again.”

Around noon on May 5, 1895, a fire broke out in the grain elevator (near the current location of Peach’s Grill), which was owned by Jeremiah Little.

At the time of the fire, Yellow Springs did not have a fire department to battle the blaze. Crews were called in from both Springfield and Xenia, but neither crew was sure if they could assist. The Springfield crew had just returned from fighting a fire in New Carlisle and had not had an opportunity to rest. The Xenia crew was not sure if they would be able to get their engine to run in order to make the trip. Luckily for Yellow Springs, both crews eventually made it to help battle the raging fire. Local newspapers reported that the Springfield crew and their horses were speeding towards Yellow Springs at a mile per minute. The Springfield crew made it in record time, but the fire was much faster.

According to newspaper reports at the time, the origin of the fire was unknown. Theories were put forth that there may have been an explosion in the furnace of the grain elevator or perhaps someone dropped a lit cigar in the building. Regardless of the origin, the fire left behind a great deal of destruction on Dayton and Corry streets.

The fire spread quickly due to a combination of windy conditions and the large number of frame buildings in the vicinity. At one point, a total of nine buildings were simultaneously engulfed in flames. Among the buildings that were destroyed were the grain elevator, a livery stable, a buggy company, the Methodist Church, a saloon and several homes. Damages from the fire were estimated to be about $18,000, the equivalent of a half-million dollars today. The damages would have been much worse, but according to the Yellow Springs Torch, “The contents of all of the buildings were mostly saved by the hard work of our citizens.” A group of Antioch College students did their part to fight the fire by forming a bucket brigade, passing over 130 buckets of water.

While the fire of May 5, 1895, was not the only large fire that Yellow Springs has experienced, it did change the layout of the village. Prior to the fire, Dayton Street was the center of the Yellow Springs business district. Afterwards, in an effort to resume business as quickly as possible, many businesses began springing up on Xenia Avenue on what was once primarily a residential street.

Today both Dayton Street and Xenia Avenue are home to businesses and, unlike 120 years ago, the village has the Miami Township Fire Department on call. The building located at 116 Dayton St. (AC Service) is the only original structure on the street that was not destroyed in the 1895 fire.

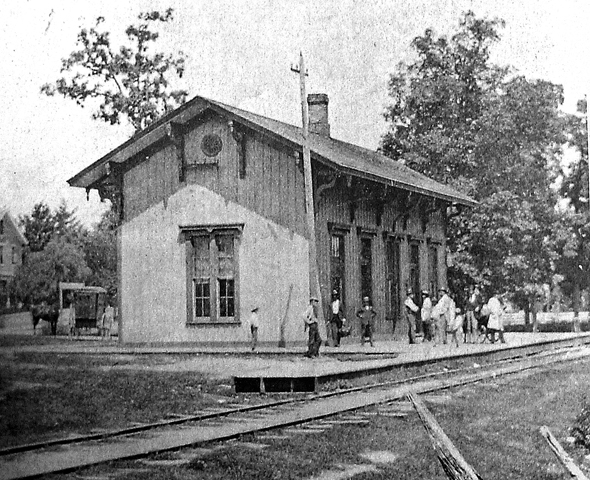

Yellow Springs’ former train station was located near the Bentino’s/Subway building. A replica was built in 2001 using its original building plans and some original trim pieces. (Photo courtesy of Yellow Springs Historical Society)

YS Train Depot

Now Chamber of Commerce

The arrival of the Little Miami railroad in 1846 provided economic growth and prosperity to Yellow Springs. The railroad brought visitors to the resorts and goods to the local businesses.

Yellow Springs Station is a replica of the 1880s train depot reconstructed in 2001, a few hundred feet north of the original location (the original was on the other side of the tracks, just behind what is today Bentino’s Pizza).

To reconstruct the station, builders used pieces salvaged from the original building by local railroading enthusiasts as well as its original building plans.

Today it serves as the Yellow Springs Chamber of Commerce, an information center and public restrooms.

Elisha Mills built the Yellow Springs House in the mid-1800s and began advertising it as a hotel soon after. It is now the site of the John Bryan Community Center. (Photo courtesy of Antiochiana, Antioch College)

Yellow Springs House

Now Bryan Community Center

The property where the Bryan Community Center is now located was once home to the Yellow Springs House. In the mid-1800s, Elisha Mills (the father of William Mills, who is known as the father of Yellow Springs) built a large brick home on this location. Later, Mills added onto his home began advertising it as a hotel. An article in a local 1850s newspaper bragged about all of the amenities at the Yellow Springs House:

“With cottages, billiard room, ten pin alley, boat, swing, barn, ice house … including 8 acres of beautiful lawn, shade with fruit trees … it had the capacity to accommodate 250–300 guests comfortably.”

In the early 1900s, the resort became the Methodist Home for the Aged. In 1902, a fire broke out and destroyed the historic building, and the home moved to Cincinnati. John Bryan High School was built on the property in 1928 and closed in 1963.

Today the building is home of the Village offices and police station.

2 Responses to “A historical walking tour of downtown Yellow Springs”

The Yellow Springs News encourages respectful discussion of this article.

You must login to post a comment.

Don't have a login? Register for a free YSNews.com account.

Wonderful old photographs! Great article.

Hey, thanks for your info! Interesting.

I’m curious about my property, located at 113 N. Winter St. I have a second lot behind it that seems to contain some ruins. I wonder if anything is know about what was going on back here.